NOTE: The documents in this section demonstrate Thomas Jefferson Carper’s and his family’s role during a very raw period in our nation’s history. Some of this material is disturbing considering society’s current understanding about the lasting impacts of slavery and its long-lasting effects on race relations. Contextual notes from local historians have been included in some places to better understand the political and social factors at play during this painful time before, during and after the Civil War on this land that we now know as “Greenway Heights”.

“Prospect Hill” Notable Facts

Located at 947 Bellview Road between Old Dominion Drive and Georgetown Pike

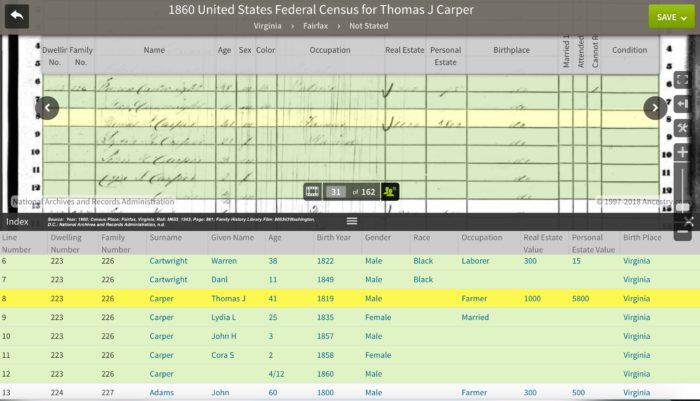

Circa 1854, “Prospect Hill” (947 Bellview Road, McLean, VA) was the original home of Thomas J. Carper and Lydia L. Carper. The Carper’s farm included the land that now comprises the Greenway Heights neighborhood. The original 415 acre farm was originally known as “Bellview.” On May 15, 1854, Thomas J. Carper was appointed head of the Roads Commission and he was also the Area III School Superintendent for Fairfax County.

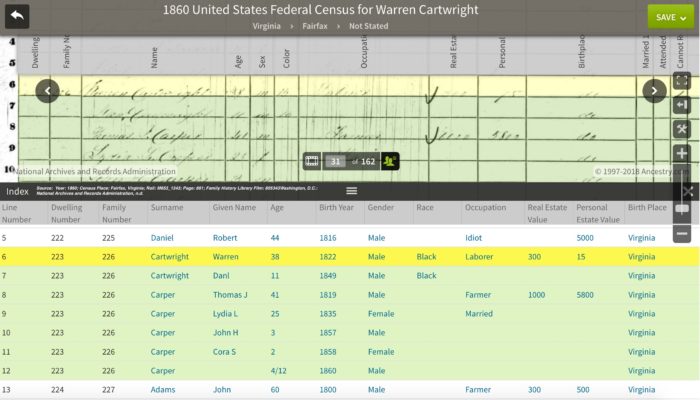

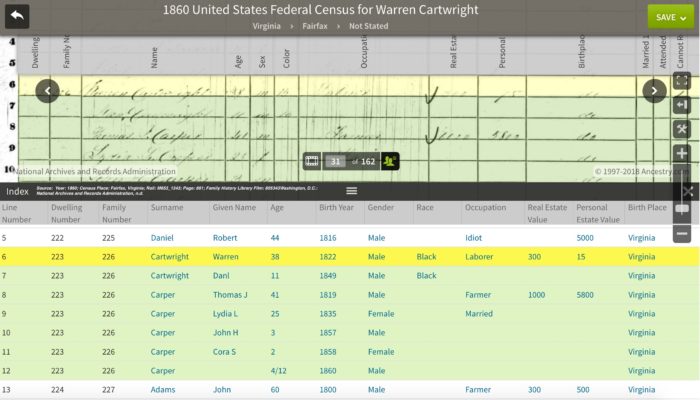

Documents confirm the Carper’s were strongly pro-Union during the Civil War. Local and federal records confirm Thomas J. Carper owned and emancipated some slaves prior to the Civil War that began in 1861. The 1860 Census also indicates two free black persons living at the Prospect Hill address: Warren Cartwright (age 38) – who owned $300 in real estate – and Danl Cartwright (age 11). (Contextual Note: According to Andrew M.D. Wolf, author of “Black Settlement in Fairfax County”, the cost of slaves was growing exorbitant before the war and “slavery was a declining institution in the District, Southern Maryland and Northern Virginia when the war broke.” Fairfax County was one of the northernmost counties in the South, with free states and the District of Columbia located just across the Potomac river. Rather than rely solely on expensive slave labor, many farmers in Fairfax County found it more affordable to have family members and hired day laborers work side by side their slaves.

Three child slaves emancipated by Carper in 1855 were required to register with the Fairfax County Court Clerk, and their names were written in the Registration of Free Negroes book. According to Victoria Thompson with the Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center, this served two purposes:

1. Emancipated slaves could prove that they were free in case someone tried to pretend the freed person(s) in question were enslaved to them.

2. The courts knew where the emancipated slaves were living and if they had permission to stay in their county of registration. (Contextual Note: Many whites had a continued fear of slave rebellion after the 1931 Nat Turner uprising when 55 whites were killed by about 50 slaves led by the deeply religious Black preacher.)

CLICK HERE: Register of Free Negroes, p. 223 & 224

CLICK HERE: Fairfax Court Order Book 1852, p. 397, April 16th, 1855

CLICK HERE: Fairfax Court Order Book 1852, p. 398, April 16th, 1855

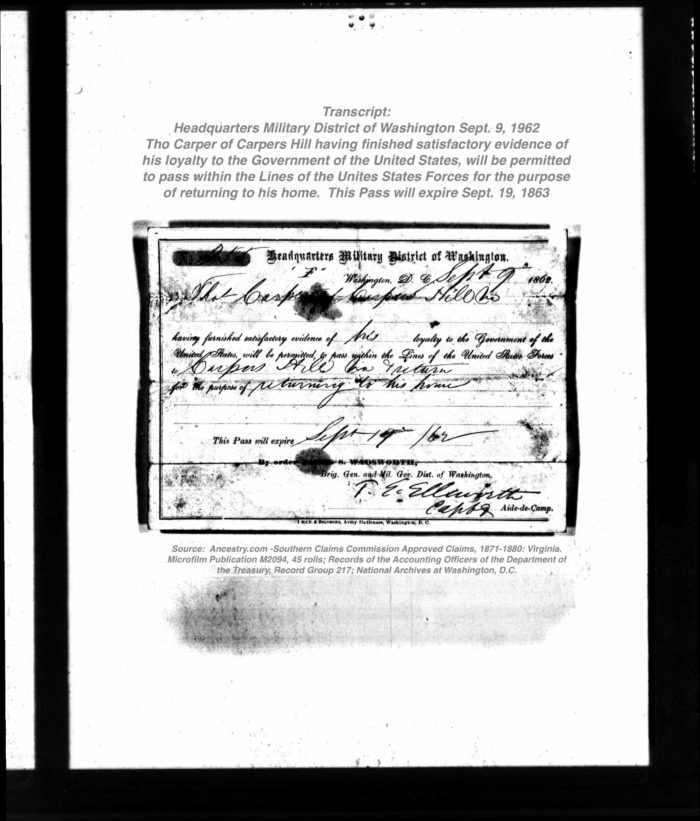

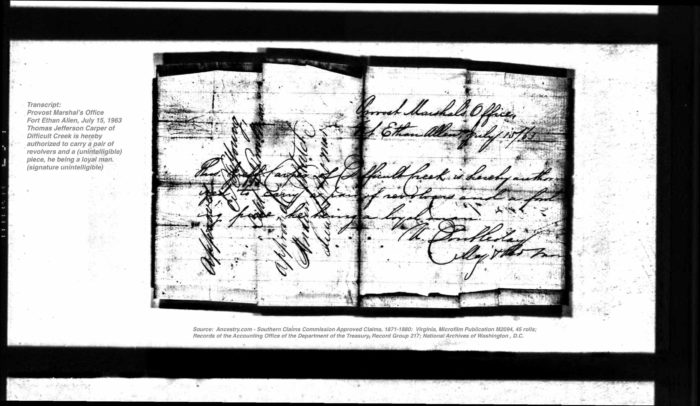

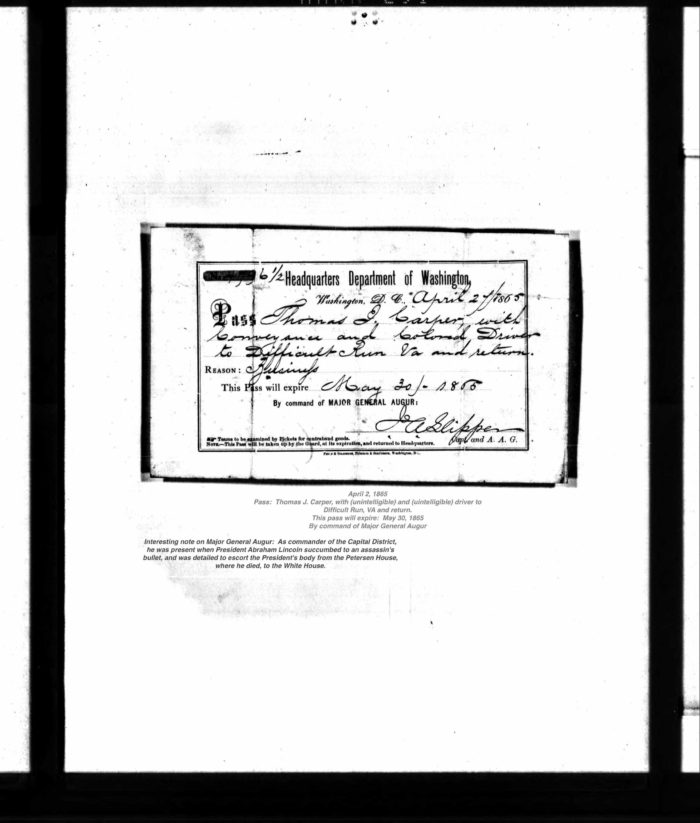

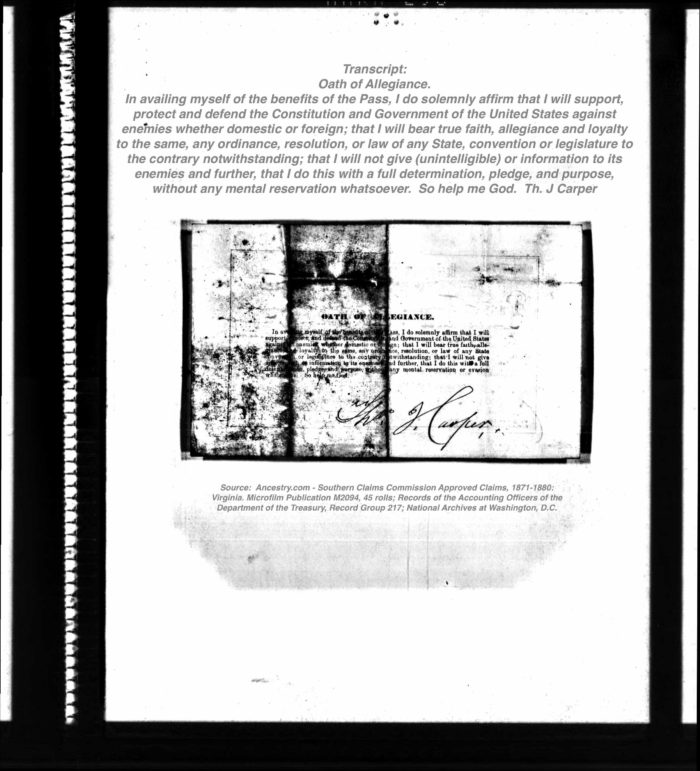

During the Civil War, Thomas Jefferson Carper received multiple passes from the provost marshal at Fort Ethan Allen to travel to and from Washington, D.C. He was also given permission to travel with guns to protect himself as he was constantly threatened by Confederate soldiers. Additionally, Rebel troops threatened to burn down “Bellview” house later known as “Prospect Hill”, but it survived thanks to the intervention of Carper’s neighbor who was a Southern sympathizer.

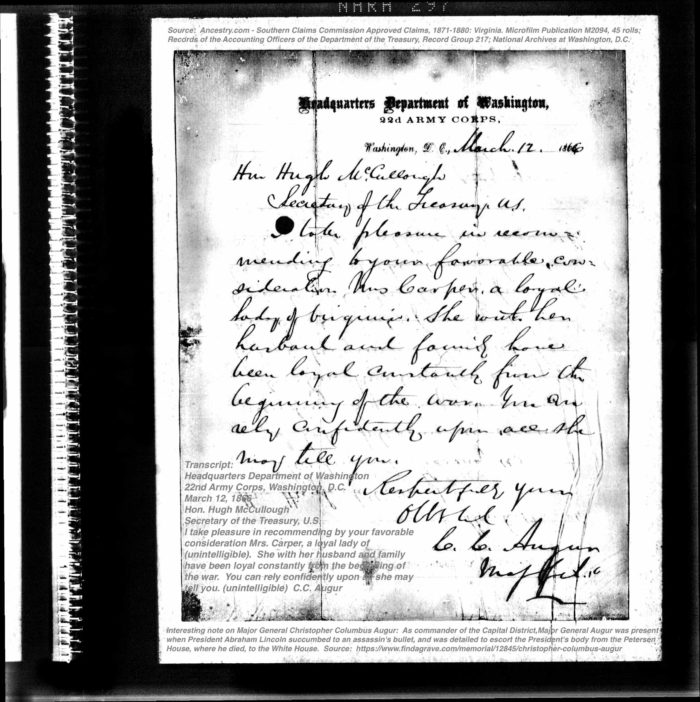

Union Major General Christopher Columbus Augur attested in writing to Thomas and Lydia Carper’s loyalty to the United States government. Interestingly, Major General Augur was present when President Abraham Lincoln succumbed to an assassin’s bullet. Augur was also detailed to escort the President’s body from the Petersen House, where Lincoln died, to the White House.

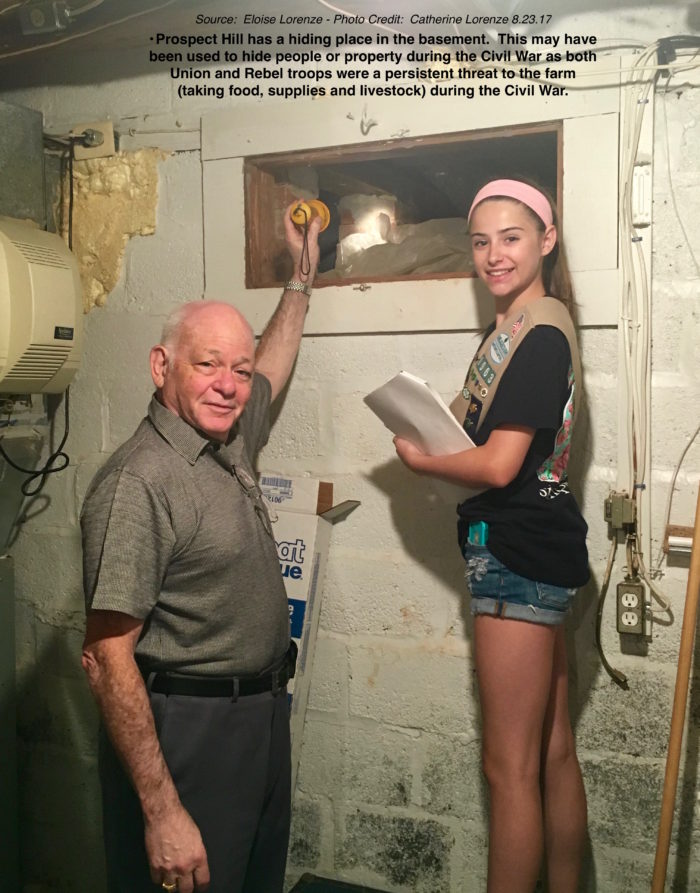

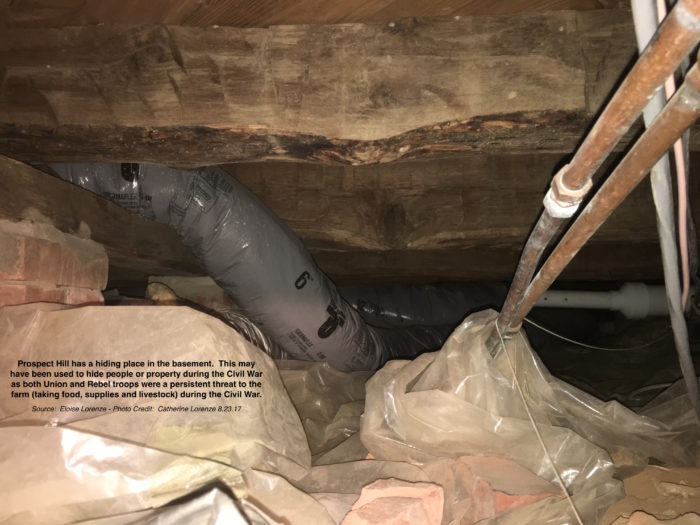

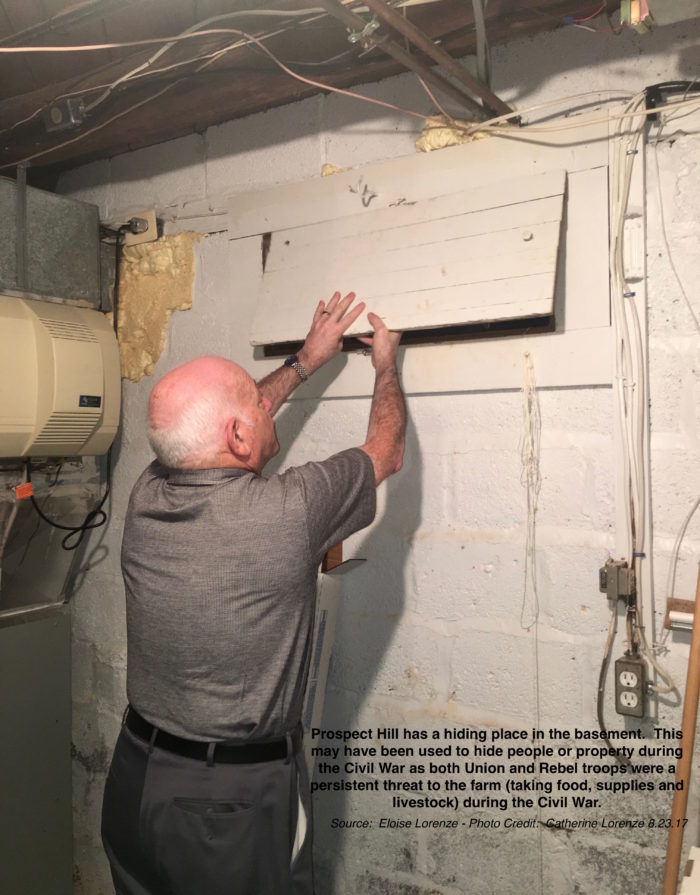

Prospect Hill has a hiding place in the basement. This may have been used to hide people or property during the Civil War as both Union and Rebel troops were a persistent threat to the farm (taking food, supplies and livestock) during the Civil War.

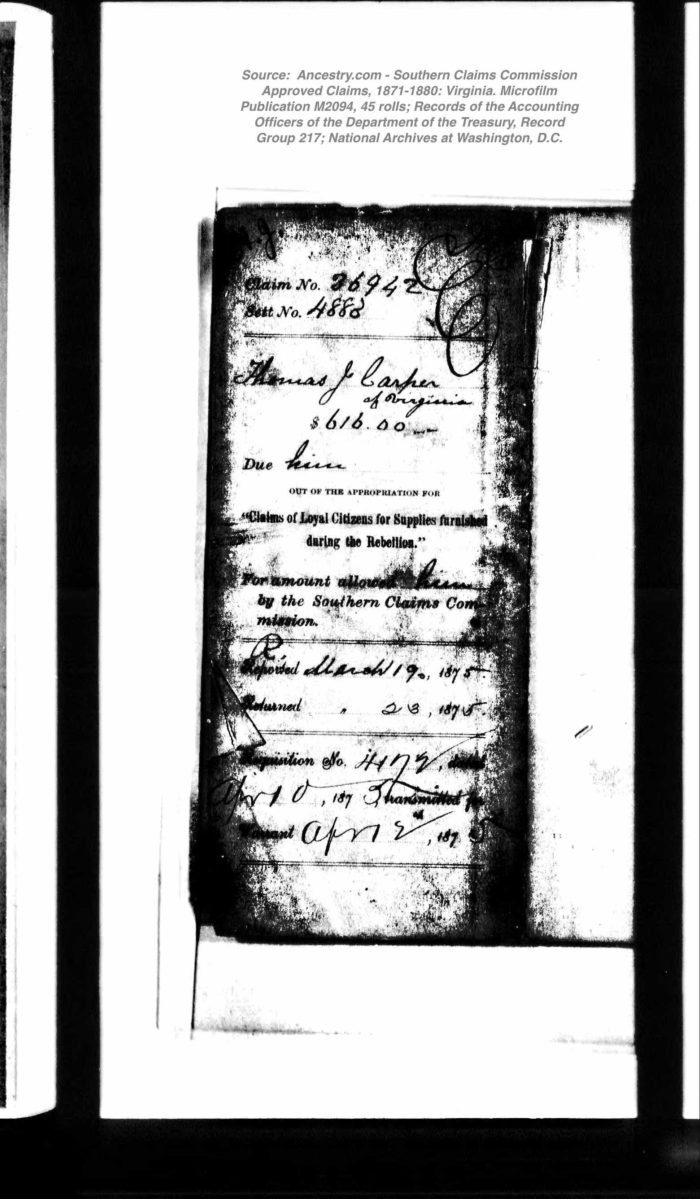

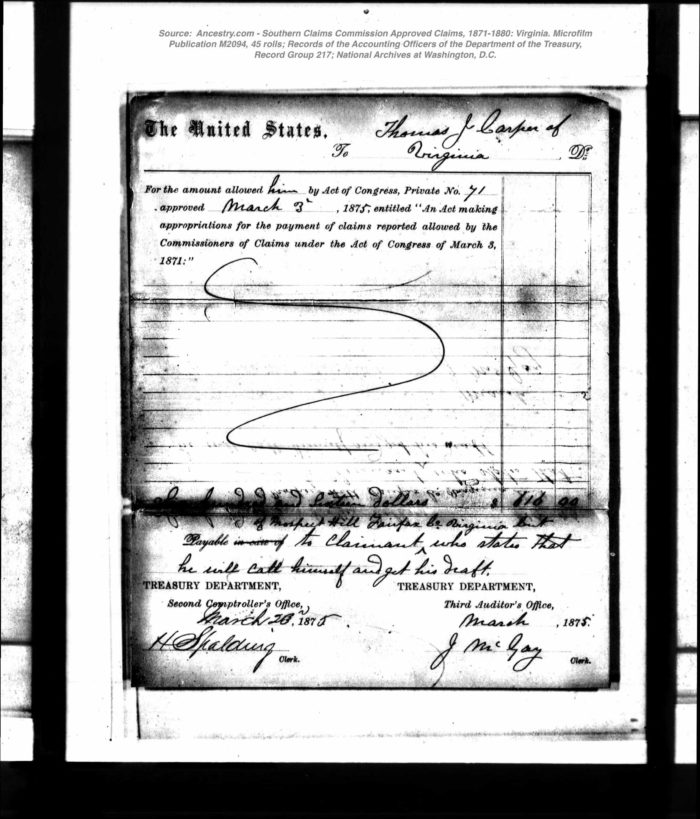

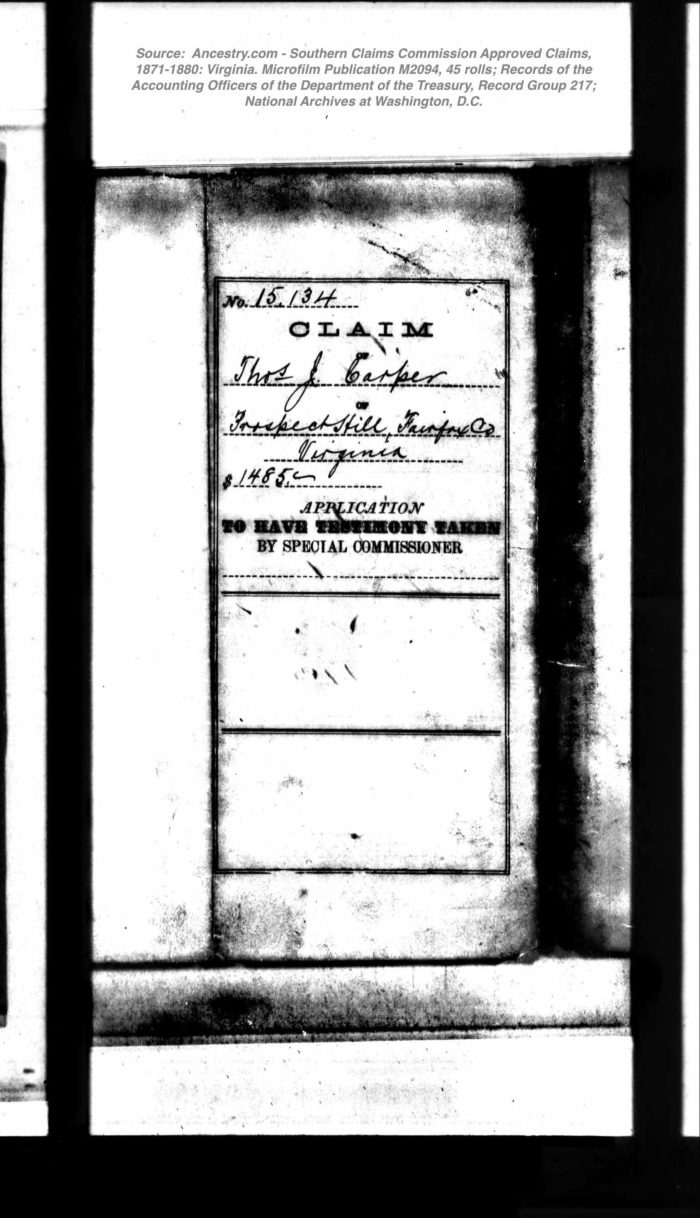

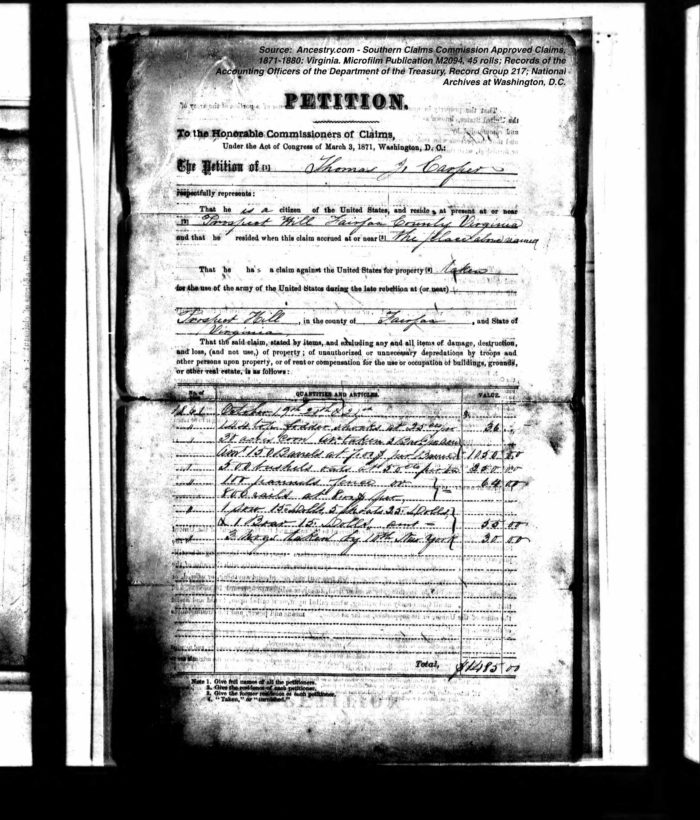

Following the War, the Southern Claims Commission confirmed the Carper’s loyalty to the Union and reimbursed them $616 for property losses suffered when Union troops camped out on Carper’s land taking corn, oats and hogs and damaging property including fence rails. Carper had originally claimed $1485 in damages.

It is significant that Thomas J. Carper was reimbursed by the U.S. Government for a portion of his losses because most civilians who applied to the Southern Claims Commission were denied. Determinations of loyalty to the Union were done by inquiring into a civilian’s reputation, checking their voting record on Secession and by asking the civilian’s neighbors, family, slaves and even soldiers he met for references. Here are some of the transcribed portions from Carper’s Southern Claims Commission application:

Page 38 – James Oliver – deposed Sept. 14, 1874 85 years old – knew TJ Carper for 50 years or more: “He always contended for the Union government and kept away from the Confederates. He was always spoken of as a loyal man to the United States.”

Page 41 – Richard H. Follin, age 47 – famer – deposed Sept. 15, 1874: “When I saw the troops getting the corn they were camped in the field and scattered through the corn.”

Page 43 – James Thomas, age 35” “I was formerly the slave of Mr. Carper. I am working for him now and have been this (unintelligible). My family lives in Washington, D.C. and I (unintelligible) this once (unintelligible) a week and that is my home. I am not in his debt. I am not in any way (unintelligible) in this claim of allowed. I know Mr. Carper to be a loyal man during the War form the beginning and he advised me to flee to Washington to keep from being taken south and he afterward advised me to get employment with the government and I did.” – Page 43 from Caper’s Southern Claim Commission

Census and deed records document that Thomas Carper sold part of his land to another of his former slaves, Warren Cartwright. Here is what Curtis L. Vaughn wrote on page 178 of his George Mason University dissertation, “Freedom is Not Enough: African Americans in Antebellum Fairfax County”:

“In 1858, Warren Cartwright, age thirty-eight, purchased four acres of land from Thomas Carper, age forty-one, for $100. The property sold was a small part of Carper’s land holdings. Warren Cartwright was not registered as a free African American in Fairfax County records, and the origin of his freedom is unknown. Three years earlier in 1855, Thomas Carper had freed two slaves named William and Daniel. In his manumission deed, Carper explained that they were the children of a slave named Mary whom he acquired in 1844 along with another woman named Anna Maria. In 1860, Carper still owned ten slaves, nine of whom were listed as mulattoes. Carper’s reason for the manumission of William and Daniel and their ancestry is unclear, although they may have been related to Warren Cartwright. In 1860 Cartwright gave a deed of trust in the amount of $110 in favor of Carper, even though he and 11 year-old Daniel Cartwright are listed in that year’s census as living in the Carper’s household. Unlike most of Carper’s slaves, the census describes the two Cartwrights as “black” indicating that they were not related to Carper. The whereabouts of William is unclear. One possible explanation is that William and Daniel were Warren Cartwright’s children by the slave named Mary. If the freedom of Cartwright’s mother dated prior to 1806, he would not have been threatened with deportation from Virginia; however if Mary had been manumitted, she may not have gained permission to remain in the state. If still living in 1860, William would have been around fourteen, an age at which he may have felt compelled to leave the area, but eleven-year-old Daniel might not have felt the same pressure to leave. Warren Cartwright may have been able to feed a family with the products from his small farm but his co-residence with Carper suggests that Cartwright’s four acres of land did not allow him full independence.”

Thomas J. Carper died in 1885, his wishes were to keep the land in his family and his widow Lydia complied. Over a span of about 25 years, she divided and subdivided the 415 acre farm among his heirs. Land Records of Fairfax County, Viriginia, Deed Book J-5, p. 290 show that Carper’s son, Thomas Samuel Carper, paid his mother Lydia L. Slack Carper $100 in 1890 for 30 acres of land located at the corner of Spring Hill Road and Georgetown Pike. Married to Lura Phillips Carter, Thomas S. Carter was a Blacksmith and amateur dentist – owning four sets of instruments for pulling teeth. Supporting eight children wasn’t easy and Carter died deeply in debt.

- In later years, the Prospect Hill property was divided among heirs including George Wallace Carper, Thomas J. Carper’s grandson and son of Thomas S. Carper, who inherited 110 acres at the corner of Spring Hill Road and Georgetown Pike. George Wallace Carper operated a successful dairy farm there until the 1960’s when most of the property was sold off to develop the Greenway Heights neighborhood. (He was also Chairman of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors and instrumental in getting the Georgetown Pike paved over in the mid-1930’s after it was no longer a toll road.)

- In the 1930’s, then owners Hilda and Manning Gasch remodeled the house and added an extension to it. Gasch is a notable figure in our area as he was instrumental in raising private funds to pave over the former Great Falls and Old Dominion Railroad to become Old Dominion Drive. Gasch’s father, Herman, was also pivotal to our local history because he worked with Lucy Madeira in orchestrating the sale of the Georgetown Pike to the state of Virginia for $500 ending its status as a toll road. Manning Gasch also used to own and live in the now abandoned property located at 8120 Georgetown Pike.

- There have been two reported sightings of a female ghost on the property – one as recently as July 2017. Perhaps it is the ghost of Lydia L. Carper. She died of a broken neck in 1918 after she fell following a bout of pneumonia. However, she did not die at Prospect Hill. Following the death of her husband Thomas J. Carper, Lydia built a house very close by on land overlooking the Great Falls and Old Dominion railroad tracks. (NOTE: This was the Prospect Hill RR stop located at what is now about 8354 Old Dominion Drive – just past Kimberwicke Drive before Bellview. See uploaded photo of the Prospect Hill RR stop under the Old Dominion Railroad section on this website)

- Prospect Hill’s current owner Howard Forman is the neighborhood association treasurer and is loved for his wonderful Halloween decorations that cover his lawn every October. Mr. Forman says Prospect Hill is a very special house, but it takes a lot of money to maintain. He feels it is important to keep it in good condition and respect its unique history to our area.

Sources:

- Lynn C. Colton and Jane E. Partridge, “The Carper Property, McLean, VA” May 1993 American Civilization Department, Langley High School: 2-4, 35

- Interview with Howard Forman, current owner of Prospect Hill, and Elaine Weinstein – Eloise Lorenze, August 23, 2017.

- Registration of Free Negroes – Commencing September Court 1822, Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center.

- Court Orders of Fairfax County, Virginia, 1855 – Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center.

- 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules – M653: National Archives and Records Administration.

- 1860: Census Place: Fairfax, Virginia; Roll: M653_1353; Page: 861; Family History Library Film: 805343, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration.

- Southern Claims Commission Approved Claims, 1871-1880; Virginia. Microfilm Publication M2094, 45 rolls; Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury, Record Group 217; National Archives at Washington, D.C.

- “Freedom Is Not Enough: African Americans in Antebellum Fairfax County” by Curtis L. Vaughn, GMU Dissertation – 2008

- “The Civil War in Fairfax County: Civilians and Soldiers” by Charles V. Mauro.

- “Black Settlement in Fairfax County, Virginia During Reconstruction” by Andrew M.D. Wolf, Fairfax County Public Library, REF. VIR. 975.29W.

- Lydia L. Carper Certificate of Death, Commonwealth of Virginia, Board of Health, File #39373, Dec. 17, 1918.